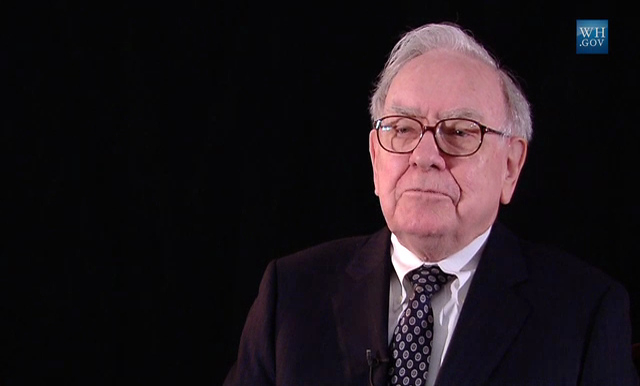

Warren Buffett on Saturday released his annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, covering the year 2017. This year it struck me as newsworthy more for what was omitted than for what was in there.

Despite Buffett's Democratic-leaning politics, there was nothing in the letter complaining about President Trump. No pleas for free trade, no pleas for immigration reform to accommodate the "dreamers," no pleas for gun control, no major complaints about the tax law (though some brief discussion of how it affects Berkshire). No mention of the #MeToo movement, though there is a borderline inappropriate comment in Buffett's letter about how board members encouraging CEOs to consider possible acquisitions is "a bit like telling your ripening teenager to be sure to have a normal sex life."

Nor was there any discussion of Berkshire's selling of its roughly $10 billion stake in IBM. There was no discussion of the problems at Wells Fargo, which at year-end was Berkshire's largest single common stock investment, with a stake valued at $29 billion. Buffett previously has been all too happy to testify to shareholders about how "very well-run" a bank Wells Fargo was. There was no discussion of the joint health care project that Berkshire Hathaway, Amazon, and JP Morgan Chase announced recently.

I did think Buffett made an interesting and valid point when discussing the relative merits of stock and bonds. As he put it:

Investing is an activity in which consumption today is foregone in an attempt to allow greater consumption at a later date. "Risk" is the possibility that this objective won't be attained....

I want to quickly acknowledge that in any upcoming day, week or even year, stocks will be riskier – far riskier – than short-term U.S. bonds. As an investor's investment horizon lengthens, however, a diversified portfolio of U.S. equities becomes progressively less risky than bonds, assuming that the stocks are purchased at a sensible multiple of earnings relative to then-prevailing interest rates.

It is a terrible mistake for investors with long-term horizons – among them, pension funds, college endowments and savings-minded individuals – to measure their investment "risk" by their portfolio's ratio of bonds to stocks. Often, high-grade bonds in an investment portfolio increase its risk.

That strikes me as good advice.