As the Federal Reserve's Open Market Committee approaches its next meeting on December 12 and 13—the last regularly scheduled meeting of 2023—Chairman Jerome Powell and his team will be making a decision about interest rates after taking a careful look at the economic data.

One key ingredient in both the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index that measure inflation is rent. We're not talking here about the imputed rent of owner-occupied housing, which is a story in its own right, but about rent paid by tenants of apartment buildings and other rental housing. Rent of that sort is about 7.5 percent of total consumer spending covered by the CPI market basket as of December 2022, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

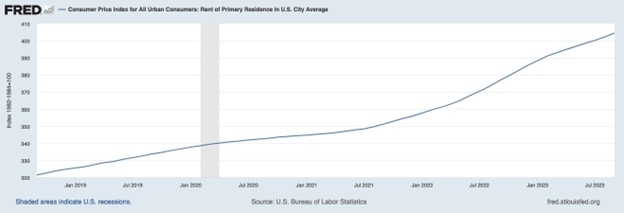

If you look at the most recently available federal government numbers on this, they show rent going up. The slope is flattening, but it's still positive.

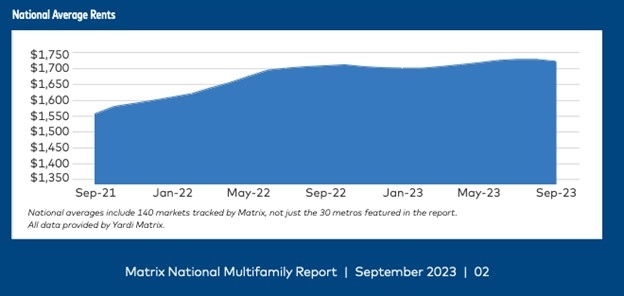

Privately collected data tells a different story. YardiMatrix issued a report on October 10, 2023 that found "Weighted down by the slowing economy and a heavy delivery pipeline in some markets, U.S. multi-family rents dipped in September. The average U.S. asking rent fell $6 to $1,722 during the month, while year-over-year growth fell to 0.8%, down 60 basis points from August." The YardiMatrix rent chart looks like this:

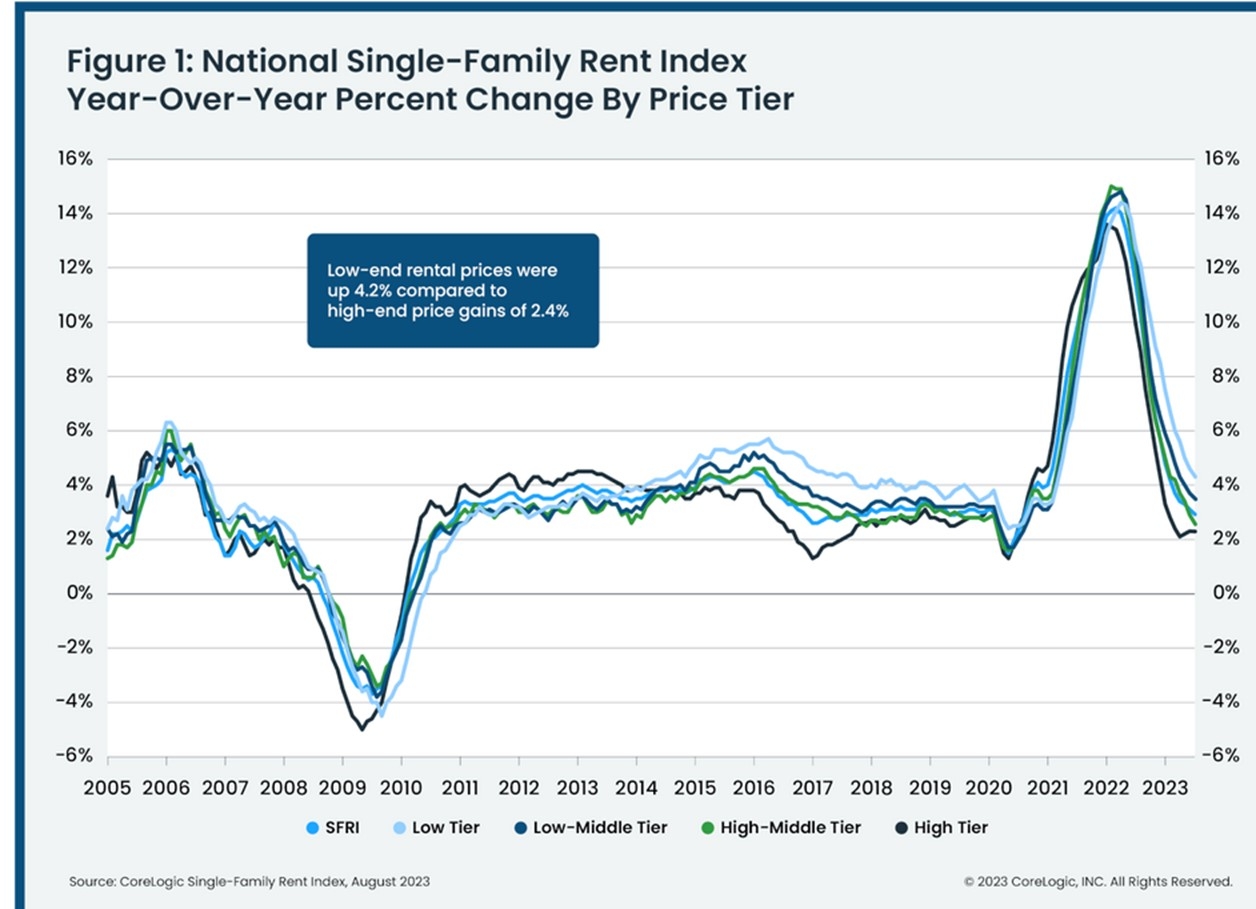

Nor is YardiMatrix the only private data collector whose data is telling a different story than that of the rent that is being reported in CPI. Here is some rent data from CoreLogic, another data provider. It also shows prices moderating:

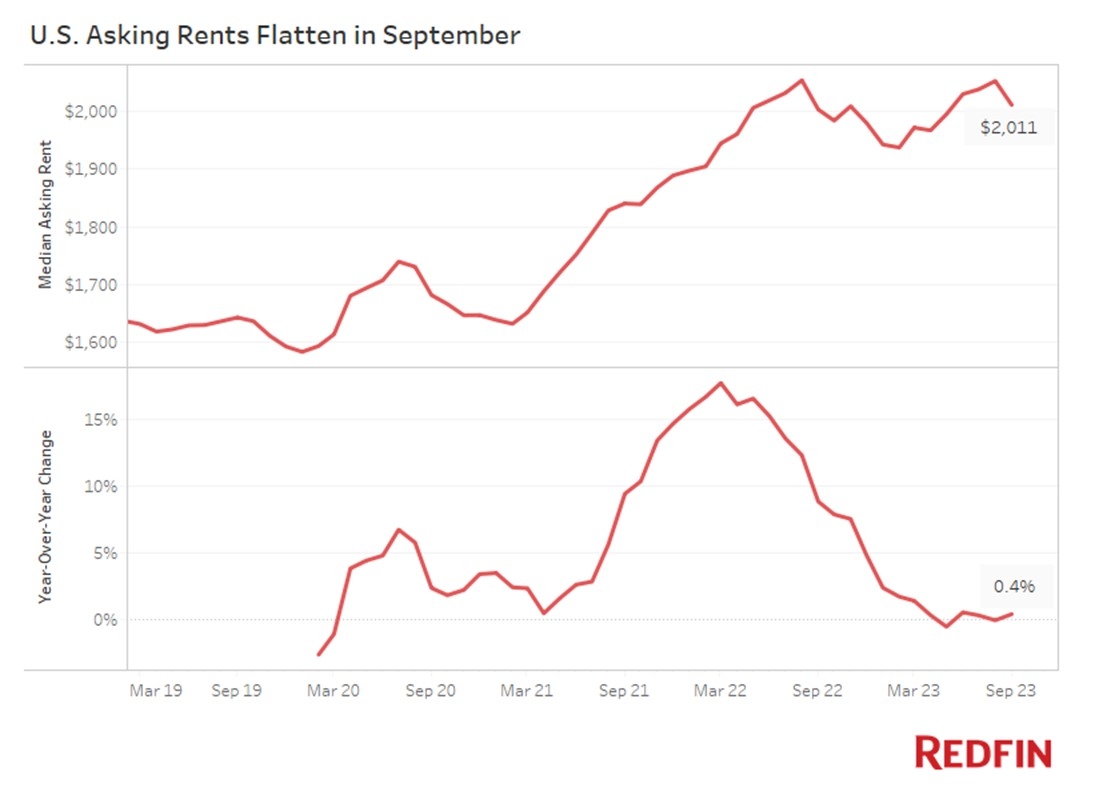

A third private-market data source is Redfin. It recently reported, "The median U.S. asking rent rose 0.4% year over year to $2,011 in September—the sixth straight month in which rents were little changed from a year earlier... The median asking rent fell 2% from a month earlier in September." A Redfin economics researcher, Chen Zhao, explained, "Rents have flattened because a boom in apartment building in recent years has flooded the market with supply." Here's what the Redfin charts look like:

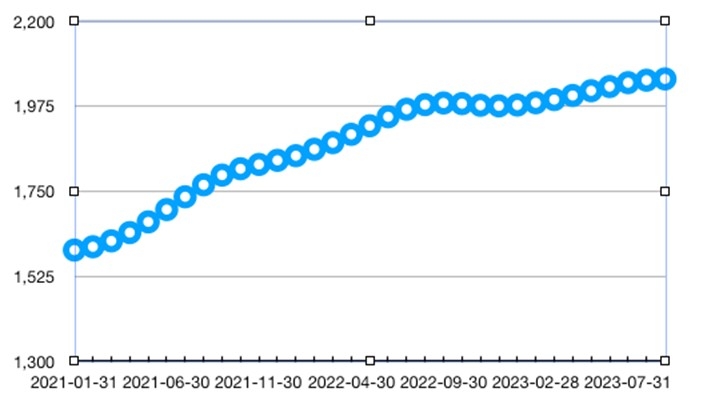

Finally, a fourth private-sector source has a somewhat similar story. Here is "ZORI," or the Zillow Observed Rent Index (Y axis is in dollars).

The website MicroMacro says that "The Zillow Observed Rent Index (YoY) usually leads the rent component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) by 6-12 months. Since rent prices account for the largest proportion of CPI and PCE, the Zillow Rent Index can be seen as a leading indicator for both."

What accounts for the different stories being told by the private data and the government data? A 2023 research paper from the Boston Fed explained that "CPI shelter typically lags market rents." The reasons are technical and have to do with the way the Bureau of Labor Statistics collects the data: "each month, the BLS surveys a sixth of its sample pool. These households were last surveyed six months beforehand. The BLS sets the month-to-month change in CPI shelter to be one-sixth of the change in rent for these households in the six months since they were last surveyed. Therefore, if every household in the sample experiences a large rise in their rent in a specific month, it will take an additional five months for this increase to fully pass through into CPI shelter. Second, the housing survey measures average rental prices for all renters—new and existing—whereas market rents measure only rental prices for new tenants. Rents for existing tenants are likely to lag rents for new tenants because landlords pass on rent increases slowly." The Bureau of Labor Statistics explains it: "The CPI program collects rent data from each sampled unit every 6 months."

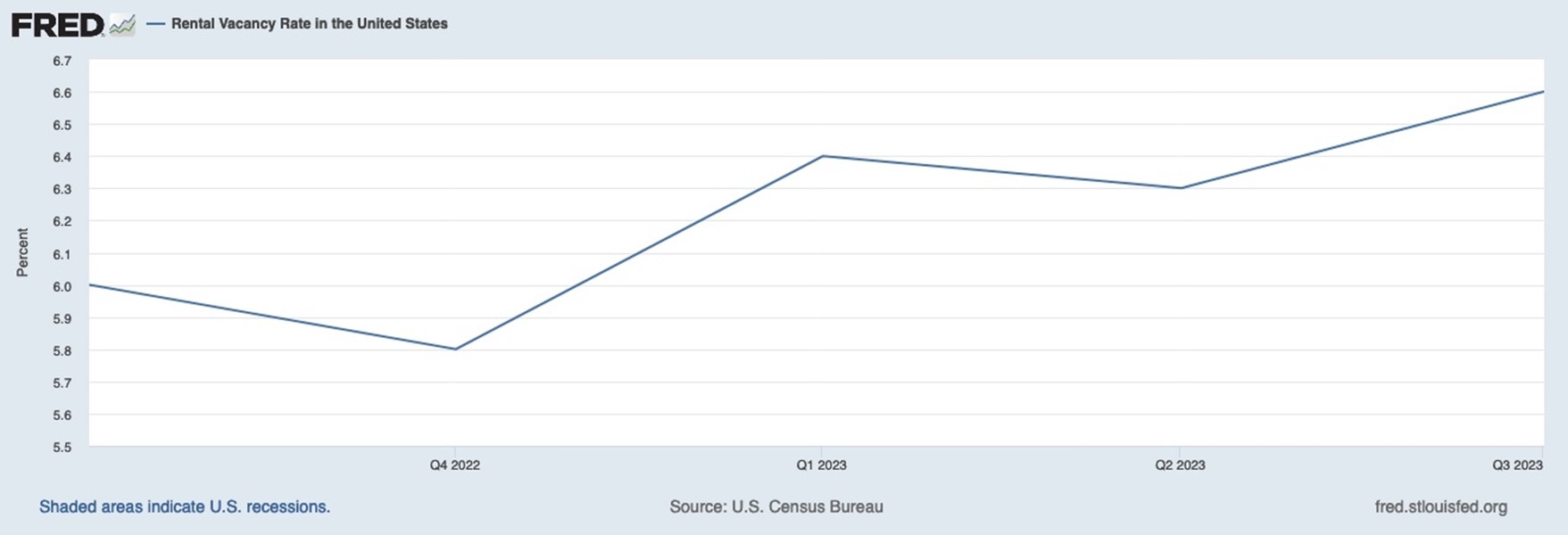

The rent story is a story about supply and demand. One government-collected statistic that might be helpful is one that isn't part of the inflation data but might eventually be reflected there.

Rising vacancies suggest that rents will eventually flatten or sink.

A couple of additional data points support this story. A November 1 earnings call transcript from Equity Residential (NYSE: EQR), a publicly traded owner of apartments: "In terms of the specific conditions on the ground in San Francisco and Seattle, as we stated previously, we have had little to no pricing power throughout the year... Over the last six weeks, however, these markets have slowed more than normal, which has resulted in larger price reductions than seasonally expected, characterized by both declining rates and increased concession use." By "concessions," Equity probably means offers like "one month free" or "half a month free," which are all over real estate rental websites these days (Boston, DC) , but which are hard to capture accurately in every-six-month government data collections. Meanwhile, Congress, the Department of Justice, and the press are pushing for an investigation of a private-equity-owned software, RealPage's YieldStar, that critics say is a way around antitrust restrictions on price-collusion in rent-setting. A recent Bloomberg article about how "Rents Are Falling in Some US Cities, Thanks to New Apartment Construction" paraphrased RealPage's chief economist, Jay Parsons: "CPI shelter tends to lag the rental market, so it should continue to fall as more new supply becomes available."

What to make of all this?

First, one hopes the Fed policymakers will be sophisticated enough to take the vacancy and private market-data into account, and not to make the mistake of raising interest rates in response to flawed, six-month-old government rent-inflation data.

Second, while the story of declining or moderating rents may be a good one for slowing inflation and flattening or eventually declining interest rates, it also may have a downside for investors and lenders who have put money into apartment buildings on the basis of overly rosy scenarios about steeply escalating rents. With office and retail real estate also coming under pressure, developers who are leveraged and lenders who are exposed might find themselves needing to restructure.

Third, it's all an example of how the many firms and individuals that make up the private market economy—renters, developers, investors, data vendors—have a way of problem-solving around housing supply and prices in a way that works more efficiently and more quickly than anything that can be done by even the most brilliant and industrious bureaucrats and central planners in Washington. The incentives and information are all better in the private sector. It's cause for some humility at the Fed and in the executive branch when it comes time for inflation-measuring and interest-rate setting.